PLACE voting: a graphical example

How we can represent all voters, fix gerrymandering, reduce polarization, and increase voter choice.

I’m going to show you how it’s possible for a voting method to represent almost 100% of voters, using a voting method called PLACE voting (which stands for “proportional, locally-accountable, candidate endorsement voting). To start with, here’s a diagram that you may have already seen in another context: as an explainer for gerrymandering.

Look at the first image: “Perfect representation”. With these districts, 98% of voters get a representative from their favorite party (only the one gray independent voter does not). So approaching 100% is possible; all it takes is a way to group similar voters together. Even if the number of voters of each color wasn’t a perfect multiple of 10, you could still guarantee that 90% or more in this 5-seat “state” would be represented by their favorite party; more, if there were more districts.

Now, look at the second image: a natural gerrymander in favor of Orange. Over 1/3 of the voters voted against their local representative. What if we transferred those votes to other candidates of the same color? That’s what PLACE voting does. Here’s the basics of how it works:

- Voters each choose one candidate.

- Any candidate with under 25% of the votes from their own district is eliminated. Those votes are transferred to the similar candidate with the most direct votes. (For now, “similar” will just mean “same-color”; I’ll add more details later. Of course, votes are never transferred to candidates who are already elected.)

- Any candidates with an average district worth of votes is elected; any votes they have above that amount are transferred; and any opponents they had in their district are eliminated.

- The candidate who is the furthest behind in their district (biggest gap between them and the local frontrunner) is eliminated.

- Repeat from step 3 as long as there are still districts with more than one candidate remaining.

- Each party assigns each district they didn’t win as “extra territory” to one of their winning candidates.

Here’s an example of how that would work. Districts are numbered D1-D5, purple and orange candidates are P1-P5 and O1–O5.

As you can see, PLACE gets the correct 60/40 Orange/Purple representation, even if the districts are drawn to favor one color. But that’s not the only advantage.

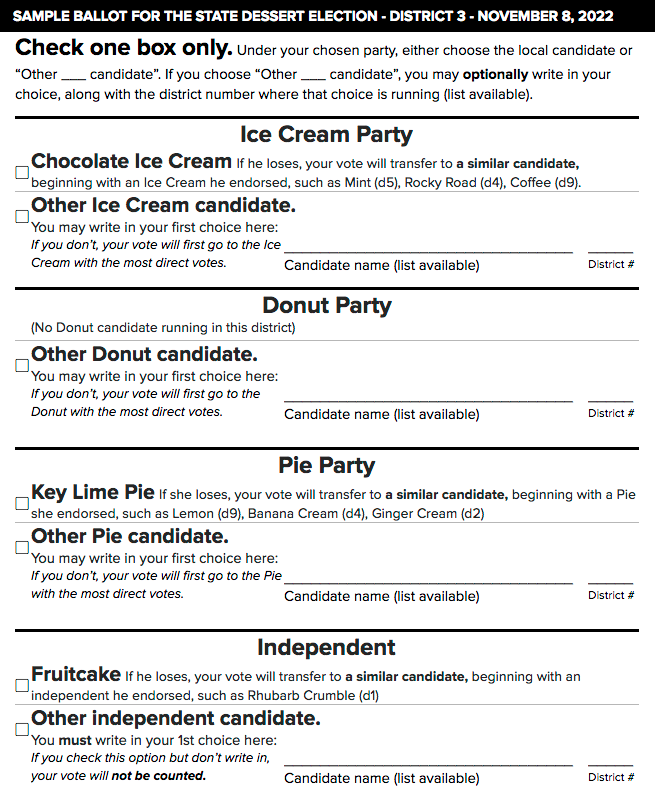

Many voters care about more than just what party and what district a candidate comes from. PLACE gives those voters more options, and helps ensure those options will matter. If you prefer a candidate from some other district, PLACE lets you vote for them, using a ballot something like this:

Also, if your candidate is eliminated, your vote goes first to one of the same-party candidates she endorsed as a “faction ally”; then, after all those are eliminated, to any same-party candidate; then, if it’s still not used, to any of the different-party candidates she pre-endorsed as a “coalition ally”. Within each of those levels, your ballot goes to candidates with more direct votes first. All endorsements are made publicly, before the election, so voters can use them to help decide how to vote. Note that even when your vote transfers to another candidate, it still “remembers” whom you voted for first, and transfers based on her endorsements not those of whichever candidate happens to currently hold it.

If you’re happy with the local candidate for your party, none of that matters much to you. But if you’re part of a minority in your party, with specific issues that are especially important to you, you can vote for the candidate who speaks to those issues and excites you the most, even if they’re not in the same district.

Let’s see what that would mean in the example above. In this case, a minority of the orange voters are “circles”. This could be an ethnic minority, or just voters with specific priorities for the party to address first. In D1 and D2, where most of the orange voters are circles, the orange candidates are also circles; and these both endorse each other as “faction allies”. Most voters make sure to vote for a candidate of the same shape, but a couple are lazy and just vote for the same-district candidate.

In this case, PLACE gives nearly 100% perfect representation, not only of parties, but even of factions within parties. Of course, in real life, each group would not be neatly divisible by the district size, so up to half of a district of voters would not be represented (perhaps a bit more if there are more than two non-overlapping coalitions of parties). But if this were used for congressional elections, half a district per state adds up to just 25/435=6% of voters; even less, if congress were enlarged.

PLACE has other advantages. It gives a fair chance to independents and third parties, but since they have to clear 25% in their home district, it doesn’t lead to excessive party splintering. Even minority communities which are too small elect their favored representative get a stronger voice, as other candidates seek endorsements from their leaders. Since it uses existing districts and voting machines, it’s not very disruptive, and legitimately-popular incumbents don’t have to feel threatened by it. And the lack of redistricting also means it could be easily implemented by either state or federal law.